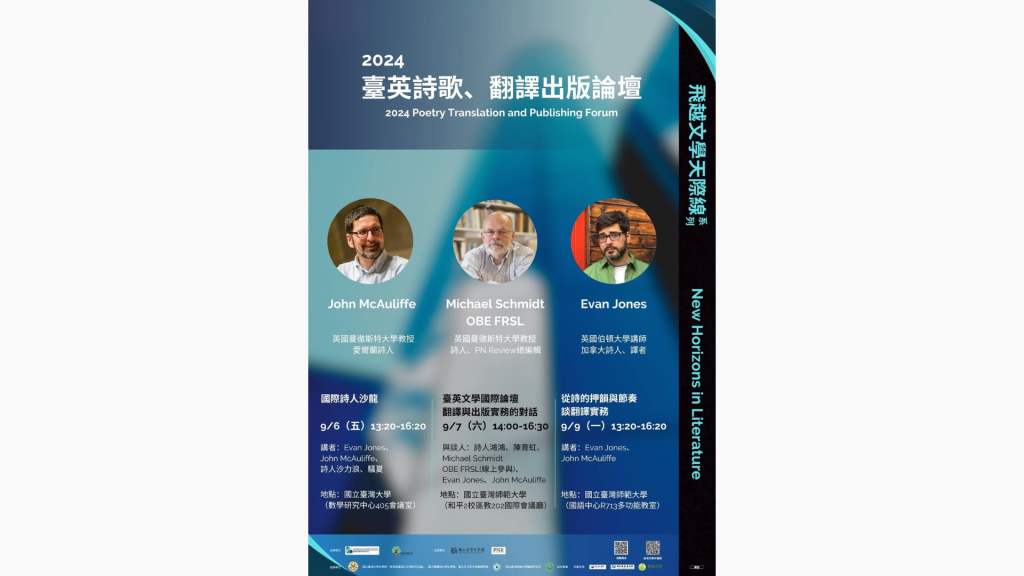

I arrived at the International Conference Hall about an hour before the Open Forum on Translation and Publishing of Poetry was scheduled to begin. Having left my bags at my seat, I went back outside to have a snack, where I saw Professor John McAuliffe and Dr. Evan Jones having lunch in the lobby. For both Professor McAauliffe and Dr. Evan Jones, this was their first time in Taiwan, and they seem to have been well taken care of, enjoying many of the sights, sounds, and diverse cuisine of Taipei in between scheduled events.

We chatted for a while, about their experiences so far, and about my personal area of interest – postcolonialism and Indigenous writing and representation. But I felt out of my depth in a discussion about poetry, so we left the main subject – the role of poetry translation and its publishing – for the forum itself.

Michael Schmidt’s face towered over the audience and our four panel members as he made his opening remarks remotely from the UK, pointing out the risks and rewards of poetry translation as he saw them. He brought up Robert Frost, who claimed that “poetry is what is lost in translation,” but Schmidt disagrees, saying that “poetry is what is carried across.” Though I didn’t quite grasp it at the time, this point would return again and flower into a bigger conclusion.

Chen Yu-hong suggested that, “Translating poetry is more difficult than translating novels. Of course, you need the source text and the target language, but you also need a third language – the language of poetry… That’s why they say it’s always better to have a poet to translate poetry.”

Hence, it may not be too surprising that Dr. Jones has been rendering Taiwanese poems in English for over a year now, despite not knowing any of the languages of Taiwan. He connects with a fellow scholar in Taiwan to grasp the content of the poem, then works as a poet in the target language, providing the language of poetry which Ms. Chen described, to make it effective and touching in the target culture. This, maybe, is what Michael Schmidt meant when he said that “poetry is what is carried across.”

This is the key to the translation of poetry, and I would say, any literature at all. Perhaps it is also why Frost implied that poetry cannot be translated, and academic translations rarely take on life as pieces of art. A machine may be able to translate content, but it takes a poet or writer versed in that third language, to create something moving in the new language.

Speaking of machines, I was surprised and heartened by the casual way in which all the panelists dismissed the threat posed to their field by large language models. I myself have never tried using an LLM to write or translate poems – but the panelists had, and they made it clear that the products were not impressive, because there is simply not enough good poetry in the world to train a language model on. Chen Yu-hong’s response to suggestions to use AI was, “If we have a good translator, why do we need AI? We have brains!” And on a deeper level, Hung Hung asked why we read and write poetry in the first place, if not to move and be moved by another person?

To those unfamiliar with the field – such as myself – the intricacies and potential of poetry may seem limited. Indeed, one setback poetry has faced is that it is no longer as visible in our media alongside the book reviews or the opinion pieces of mainstream dissemination, unless your social media feed has learned to provide it; as Professor McAuliffe put it, “prize culture” has overtaken “newspaper culture.” Poetry has been corralled into the poetry category, out of sight, out of mind for many of us. Perhaps for that reason, poetry journals remain very important to poet circles, in ways that they no longer are for publishing short stories or novels.

And yet, everyone in attendance seemed to agree that poetry still retains advantages over other forms of media in cultural transmission. Dr. Jones mentioned the speed of their travel: novels can take months or even years to work their way through the publishing, translation, and republishing process, by which time they may lose relevance in the news cycle or wider culture. But poems can bridge the gap in just days or weeks. If our goal is to create emotional connections by going deeper than surface level in sharing and appreciating cultures, then poetry seems worthy of more attention than it is given.

Furthermore, its relative neglect, or “cultural rarefication,” means that composing and translating poetry is a labor of love, not a commercial enterprise. Whatever the content or origin of a poem, we can be sure that it was created and transmitted with genuine emotional intent. That authenticity is something to be treasured in the modern world.

All this, to me, undercuts the idea that the translation of poetry is somehow impossible or unneeded. In fact, I would go so far as to say that the further away two cultures are from each other, the more necessary and effective it becomes. I came away with my attitude towards poetry translation both strengthened and tempered, and convinced that it has a greater role to play in building connections between the people of Taiwan and those of other countries.

Written by Gregory Laslo